Justice Scalia's Greatest Hits in King v. Burwell Dissent

Justice Scalia's Greatest Hits in King v. Burwell Dissent

By: Patrick Hedger-Policy Director, American Encore

Today's decision to uphold subsidies in states with the federal ObamaCare exchange, in clear violation of the letter of the law, is a huge dissappointment. This means millions of Americans will continue to be subject to burdensome taxes and punishing regulations under ObamaCare. Meanwhile, the mechanics of ObamaCare will continue to put upward pressure on healthcare and insurance prices along with downward pressure on overall healthcare quality.

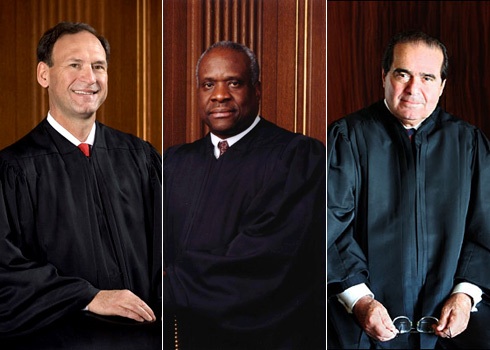

Despite all this, three Supreme Court Justices sided with the American people, the Constitution, and the rule of law. Justices Alito and Thomas joined Justice Scalia in a scathing dissent to the Court's ultimate decision. Justice Scalia's dissent makes dozens of powerful points with flawless logic and application of the law. Therefore, as disspointing as today's loss was, let us enjoy the wisdom of Justices Scalia, Alito, and Thomas and learn from their words. Here are some of the highlights of today's King v. Burwell dissenting opinion: (Find the full opinion here)

- The Court holds that when the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act says “Exchange established by the State” it means “Exchange established by the State or the Federal Government.” That is of course quite absurd, and the Court’s 21 pages of explanation make it no less so.

- This case requires us to decide whether someone who buys insurance on an Exchange established by the Secretary gets tax credits. You would think the answer would be obvious—so obvious there would hardly be a need for the Supreme Court to hear a case about it. In order to receive any money under §36B, an individual must enroll in an insurance plan through an “Exchange established by the State.” The Secretary of Health and Human Services is not a State. So an Exchange established by the Secretary is not an Exchange established by the State—which means people who buy health insurance through such an Exchange get no money under §36B.

- Words no longer have meaning if an Exchange that is not established by a State is “established by the State.”

- Under all the usual rules of interpretation, in short, the Government should lose this case. But normal rules of interpretation seem always to yield to the overriding principle of the present Court: The Affordable Care Act must be saved.

- Let us not forget, however, why context matters: It is a tool for understanding the terms of the law, not an excuse for rewriting them.

- Today’s interpretation is not merely unnatural; it is unheard of. Who would ever have dreamt that “Exchange established by the State” means “Exchange established by the State or the Federal Government”?

- Because the Secretary is neither one of the 50 States nor the District of Columbia, that definition positively contradicts the eccentric theory that an Exchange established by the Secretary has been established by the State.

- The Court’s reading does not merely give “by the State” a duplicative effect; it causes the phrase to have no effect whatever.

- Faced with overwhelming confirmation that “Exchange established by the State” means what it looks like it means, the Court comes up with argument after feeble argument to support its contrary interpretation.

- Roaming even farther afield from §36B, the Court turns to the Act’s provisions about “qualified individuals.” Ante, at 10–11. Qualified individuals receive favored treatment on Exchanges, although customers who are not qualified individuals may also shop there. See Halbig v. Burwell, 758 F. 3d 390, 404–405 (CADC 2014). The Court claims that the Act must equate federal and state establishment of Exchanges when it defines a qualified individual as someone who (among other things) lives in the “State that established the Exchange,” 42 U. S. C. §18032(f)(1)(A). Otherwise, the Court says, there would be no qualified individuals on federal Exchanges, contradicting (for example) the provision requiring every Exchange to take the “‘interests of qualified individuals’” into account when selecting health plans. Ante, at 11 (quoting §18031(e)(1)(b)). Pure applesauce. Imagine that a university sends around a bulletin reminding every professor to take the “interests of graduate students” into account when setting office hours, but that some professors teach only undergraduates. Would anybody reason that the bulletin implicitly presupposes that every professor has “graduate students,” so that “graduate students” must really mean “graduate or undergraduate students”? Surely not. Just as one naturally reads instructions about graduate students to be inapplicable to the extent a particular professor has no such students, so too would one naturally read instructions about qualified individuals to be inapplicable to the extent a particular Exchange has no such individuals.

- The Court finds it strange that Congress limited the tax credit to state Exchanges in the formula for calculating the amount of the credit, rather than in the provision defining the range of taxpayers eligible for the credit. Had the Court bothered to look at the rest of the Tax Code, it would have seen that the structure it finds strange is in fact quite common.

- Or consider, for an even closer parallel, a neighboring provision that initially makes taxpayers of all States eligible for a credit, only to provide later that the amount of the credit may be zero if the taxpayer’s State does not satisfy certain requirements. See §35 (health-insurance-costs tax credit). One begins to get the sense that the Court’s insistence on reading things in context applies to “established by the State,” but to nothing else.

- The Court has not come close to presenting the compelling contextual case necessary to justify departing from the ordinary meaning of the terms of the law. Quite the contrary, context only underscores the outlandishness of the Court’s interpretation. Reading the Act as a whole leaves no doubt about the matter: “Exchange established by the State” means what it looks like it means.

- To mention just the highlights, the Court’s interpretation clashes with a statutory definition, renders words inoperative in at least seven separate provisions of the Act, overlooks the contrast between provisions that say “Exchange” and those that say “Exchange established by the State,” gives the same phrase one meaning for purposes of tax credits but an entirely different meaning for other purposes, and (let us not forget) contradicts the ordinary meaning of the words Congress used.

- If that is all it takes to make something ambiguous, everything is ambiguous.

- Only by concentrating on the law’s terms can a judge hope to uncover the scheme of the statute, rather than some other scheme that the judge thinks desirable.

- How could the Court say that Congress would never dream of combining guaranteed-issue and communityrating requirements with a narrow individual mandate, when it combined those requirements with no individual mandate in the context of long-term-care insurance?

- So even if making credits available on all Exchanges advances the goal of improving healthcare markets, it frustrates the goal of encouraging state involvement in the implementation of the Act. This is what justifies going out of our way to read “established by the State” to mean “established by the State or not established by the State”?

- Perhaps sensing the dismal failure of its efforts to show that “established by the State” means “established by the State or the Federal Government,” the Court tries to palm off the pertinent statutory phrase as “inartful drafting.” This Court, however, has no free-floating power “to rescue Congress from its drafting errors.”

- It is entirely plausible that tax credits were restricted to state Exchanges deliberately—for example, in order to encourage States to establish their own Exchanges. We therefore have no authority to dismiss the terms of the law as a drafting fumble.

- Let us not forget that the term “Exchange established by the State” appears twice in §36B and five more times in other parts of the Act that mention tax credits. What are the odds, do you think, that the same slip of the pen occurred in seven separate places?

- The Court’s decision reflects the philosophy that judges should endure whatever interpretive distortions it takes in order to correct a supposed flaw in the statutory machinery. That philosophy ignores the American people’s decision to give Congress “[a]ll legislative Powers” enumerated in the Constitution. They made Congress, not this Court, responsible for both making laws and mending them. This Court holds only the judicial power—the power to pronounce the law as Congress has enacted it. We lack the prerogative to repair laws that do not work out in practice, just as the people lack the ability to throw us out of office if they dislike the solutions we concoct. We must always remember, therefore, that “[o]ur task is to apply the text, not to improve upon it.”

- More importantly, the Court forgets that ours is a government of laws and not of men. That means we are governed by the terms of our laws, not by the unenacted will of our lawmakers.

- It is not our place to judge the quality of the care and deliberation that went into this or any other law. A law enacted by voice vote with no deliberation whatever is fully as binding upon us as one enacted after years of study, months of committee hearings, and weeks of debate. Much less is it our place to make everything come out right when Congress does not do its job properly. It is up to Congress to design its laws with care, and it is up to the people to hold them to account if they fail to carry out that responsibility.

- The Court’s insistence on making a choice that should be made by Congress both aggrandizes judicial power and encourages congressional lassitude.

- Just ponder the significance of the Court’s decision to take matters into its own hands. The Court’s revision of the law authorizes the Internal Revenue Service to spend tens of billions of dollars every year in tax credits on federal Exchanges. It affects the price of insurance for millions of Americans. It diminishes the participation of the States in the implementation of the Act. It vastly expands the reach of the Act’s individual mandate, whose scope depends in part on the availability of credits. What a parody today’s decision makes of Hamilton’s assurances to the people of New York: “The legislature not only commands the purse but prescribes the rules by which the duties and rights of every citizen are to be regulated. The judiciary, on the contrary, has no influence over . . . the purse; no direction . . . of the wealth of society, and can take no active resolution whatever. It may truly be said to have neither FORCE nor WILL but merely judgment.”

- We should start calling this law SCOTUScare.

- Perhaps the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act will attain the enduring status of the Social Security Act or the Taft-Hartley Act; perhaps not. But this Court’s two decisions on the Act will surely be remembered through the years. The somersaults of statutory interpretation they have performed (“penalty” means tax, “further [Medicaid] payments to the State” means only incremental Medicaid payments to the State, “established by the State” means not established by the State) will be cited by litigants endlessly, to the confusion of honest jurisprudence. And the cases will publish forever the discouraging truth that the Supreme Court of the United States favors some laws over others, and is prepared to do whatever it takes to uphold and assist its favorites.